Starting a business may be one of the most exciting things you'll ever do. But it isn't something to take lightly. According to a Harvard Business School study, about three in every four business startups fail.

Naturally, entrepreneurs should do everything they can to improve their odds. Many are turning to a strategy known at the Lean Startup.

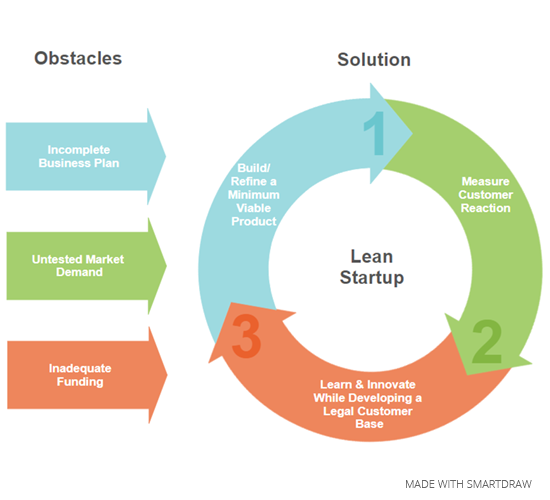

Here are three frequently cited obstacles to startup survival and how the Lean Startup strategy seeks to overcome them.

These obstacles also apply to many mature companies. The Lean Startup strategy is the answer for both new and existing organizations, according to its proponents.

Yet others disagree. Some of them strongly disagree.

To help you decide whether a Lean Startup is right for you, let's take a look at this seemingly logical concept and the reasons why some regard it as fool's gold.

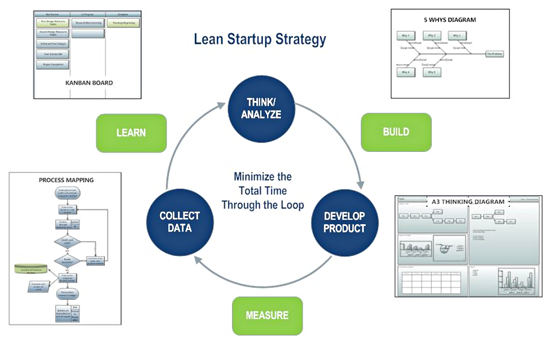

The Lean Startup strategy is actually pretty simple. It encourages the entrepreneur to get a minimum viable product (MVP) into customers' hands as soon as possible, then test it, learn from it, and refine it into a finished product. Doing this allows the business to learn what customers want and to focus its development efforts accordingly. This is known as the build-measure-learn feedback loop.

The concept was presented by tech entrepreneur Eric Reis in his book, The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. While originally geared toward technology companies, the idea has expanded to encompass nearly all industries, and is even being applied in the government sector.

The strategy draws upon the tenets of Lean manufacturing—the elimination of wasteful practices with a

focus on customer satisfaction through continuous product and service innovation.

It also applies techniques used in Agile software development—applying iterative

and incremental steps in product creation. A Lean Startup incorporates uses

of Lean and Agile diagrams such as 5 Whys analysis, A3 Thinking (which can used to create a Lean canvas—a specialized A3 thinking diagram for business models),

Process Mapping, and Kanban boards.

Here's how the Lean Startup aims to overcome the obstacles mentioned above.

Obstacle 1: Incomplete Business Plan

A recent article, "Why the Lean Start-Up Changes Everything," by Steve Blank, appeared in the Harvard Business Review. (Blank is an associate professor at Stanford University; Eric Reis is one of his former students.) It discusses the "fallacy of the perfect business plan." Blank likens the futility of trying to accurately predict a five-year business forecast to a comment Mike Tyson once made about his opponents' prefight strategies: "Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth."

According to Blank, most businesses don't survive their first contact with customers. So while existing companies execute a business model, startups look for one. The Lean Startup is "designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model."

The Lean Startup philosophy is more interested in getting a product into the hands of potential customers quickly than spending a lot of time on hypothetical business forecasting.

Obstacle 2: Untested Market Demand for the Company's Product

Developing a finished product is often a time-consuming and capital-intensive undertaking. Worst of all, a traditional approach may produce an untested product that misses the mark and results in failure of the enterprise. The Lean Startup works around this issue through the MVP and a concept known as the "pivot."

The MVP, or minimum viable product, is a product that has just enough features to be deployed for testing to early adopters. This is a group of prospective customers who are savvy enough to understand the company's vision through an early prototype model, and willing to offer feedback. The idea is for the company to avoid, as early as possible, building a product that customers don't want. Developing an MVP is the first step in the build-measure-learn feedback loop.

In a pivot, a business hypothesis about the product, business model, or engine of growth is tested. If it fails, then a corrective course of action is taken.

Creating a product in this manner becomes an iterative process between the business and its prospective customers.

Obstacle No. 3: Lack of Adequate Funding

It's no secret that most startups fail due to under-capitalization. But is it just a capitalization problem? Or is the real issue that all too frequently, startup capital is depleted during the development of an end product that customers simply don't want.

The Lean Startup approach is intentionally geared to reduce the need for heavy upfront capital investment. This is done by quickly (a) building a basic product (the MVP) for launch, (b) testing the market's acceptance of it, and then (c) iterating the product or service through innovation and customer feedback.

The concept of the Lean Startup isn't just

for startups, according to Steve Blank. In our fast-paced world, things change rapidly.

Markets face continual disruption. Businesses, regardless of size, must be adaptable.

Innovation is replacing domination (think about how new technologies

ended the dominance of Microsoft, for example).

The old "business as usual" paradigm doesn't work any longer.

Whether a start-up or an existing business, Blank is adamant about one thing:

companies have to understand what their customers want. "It's easier to avoid failure

if you build a customer-centric business. You need to get your hands dirty."

It certainly wouldn't be fair to discuss all of the wonderful things about the Lean Startup without mentioning that the concept also has detractors. One of these is entrepreneur/author Jon Burgstone. In

an article he wrote for Inc Magazine, Burgstone discusses what he sees as a major flaw in the concept of going to market with a minimum viable product.

While he agrees with the concept of customer feedback, Burgstone says that taking a "lackluster product" to the market is, well, "insane."

He points to Facebook, Google and Apple's iPod (more thoughts on this later) as examples of products that weren't the first to hit the market in their respective niche. Rather, they took similar, "lackluster" products and made them viable.

"Perhaps smart entrepreneurs should watch the efforts of lean entrepreneurs and then pull an Apple, Google or Facebook on them," Burgstone says.

John Finneran writes about software, IT, and financial services.

Unfortunately, Finneran's software startup took an opening round, Iron Mike-style punch in the nose. The first customer demo was a disaster. "Though charmingly polite, our clients were humiliated by the demo and too irritated to 'iterate' our minimum viable product with us."

There were lessons learned. Finneran calls them "unlean" lessons.

The ideas of using "early adopters" and "earlyvangelists" may be unrealistic. "For every customer or prospect we talked with, the risks of innovation (failure and losing their job) far outweigh the hypothetical benefits we proclaimed. Customers just want reasonably priced software that does its job, not help you launch your Lean Startup adventure."

Finneran offers four "unlean lessons" for anyone considering a software startup:

- Mediocre execution will kill your startup.

- Forget MVP—narrow the scope until you can develop an extraordinary product.

- Fund your marketing budget sufficiently.

- Beware of any "shrink-wrapped utopia offered by the entrepreneurial dream industry."

Is the Lean Startup a viable, valuable alternative to the entrepreneur? Or is it just another idea offering great promise but lacking real rewards?

Before I offer my $.02, I will tell you that I've done a number of business startups in my life. All of them were before I knew anything about the concept of a Lean Startup. So whatever knowledge I have is purely observational, not experiential. But to me, the concept makes a terrific amount of sense.

I'll also tell you that it's a lot easier to be a critic than an innovator. So I applaud Steve Blank and Eric Reis for their innovations.

As to the two dissenting opinions offered, I'll give John Finneran his due. At least he attempted to follow the Lean Startup formula. It clearly didn't work for him. Was this the fault of the method or the practitioner? I can't say, but I think his "unlean lessons" are worthy of entrepreneurial heed.

Both Finneran and Jon Burgstone throw MVP, categorically, under the bus. In doing so, I think they've both gone too far. I believe they've misinterpreted what an MVP is supposed to be.

Burgstone calls the MVP a "lackluster product." Have I misread or misunderstood what I've learned about the Lean Startup philosophy? I don't think so. To me, there's a huge difference between a "minimum viable" and a "lackluster" product.

For example, Burgstone cites the iPod as an example of a new device that replaced a lackluster product to dominate its market niche. This is true. But he overlooks an important historical detail. The iPod started out as an MVP—prototyped, tested, and iterated based on results of feedback. One has to wonder, had Apple focused all of its attention on developing a final product, would it have been the awesome iPod we know today? Or might it have been something... dare I say... lackluster?

The key point is this: Minimum Viable Product and Lackluster Product are not synonymous. If your product is a piece of crap, by definition, it's not viable. An MVP should be an awesome product—with the minimum feature set needed to make it worthy of testing. No more, no less.

To throw out the entire Lean Startup concept over a misinterpretation of what constitutes an MVP is, to me, a potentially huge mistake.

So, is a Lean Startup right for you? As with anything, much will be determined by the practitioner. Producing a shoddy product and hoping market testing will make it viable won't work. Insufficiently funding your startup with enough capital will, most likely, be fatal.

You have to be informed, prepared, and capitalized.

So go ahead and be Lean. But be smart, too.

And build something awesome.