Can a strategic plan truly yield bottom-line results? Or is it just a waste of time?

The answer to both questions can be yes. It's critical to plan for success. More importantly, there are steps to follow to make it happen.

Most businesses don't do any strategic planning. And, of the ones who do, most treat it as nothing more than an academic exercise. This is unfortunate. With some effort and a willingness to make hard decisions, it's possible to create more than just strategy.

It's possible to realize bottom-line results from a well-developed strategic plan that is then put into action and followed through.

Strategic planning was a management phenomenon in the late 60s and early 70s. It was being hailed as "the fountainhead of all corporate progress." Everyone, it seemed, was doing it -- or in danger of being left in the dust by the competition.

Then something happened. CEOs began questioning the effectiveness of strategic planning. One anonymously referred to it as "a staggering waste of time." Another called it "basically a plaything of staff." And strategic planning began to fall out of vogue.

What changed? How did strategic planning-once the road to corporate nirvana—suddenly become a C-suite pariah?

This question was addressed by IBM CEO Louis Gerstner back in 1973. In an article published by McKinsey & Company, "Can strategic planning pay off?" Gerstner took aim. Not at the practice of strategic planning, but at those CEOs who were failing to grasp what it entails.

According to Gerstner, the CEOs didn't see any bottom-line impact. Therefore, they considered strategic planning to be merely an academic exercise that offered no tangible, real-world results. But Gerstner laid the blame on these executives themselves. What they called strategic planning was, in his view, little more than an extrapolation of short-term financial projections.

Here's what Gerstner had to say:

"Many strategic-planning programs begin with the extension of the annual operating budget into a five-year projection. Most companies, however, soon discover that five-year operational and financial forecasts, in and of themselves, are ineffective as strategic-planning tools for a fundamental reason: they are predicated on the implicit assumption of no significant change in environmental, economic, and competitive conditions."

He offered up some reasons for why so many efforts at strategic planning fail to produce financial results--and what can be done about it.

In Gerstner's view, companies stopped engaging in true strategic planning. CEOs stopped being involved and started delegating the task. Their charges merely added a layer to the company's five-year financial plan, wrote it up in a report, and called it "strategy."

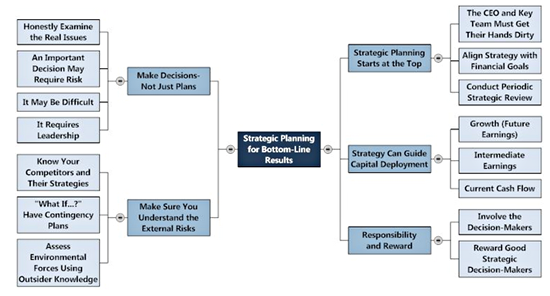

But strategy requires much more than extrapolating a budget. It requires an open, honest examination of the toughest issues the organization faces. Tough questions have to be asked. Warts may need to be exposed. This can be difficult. It can be uncomfortable. It requires leadership and decision-making. It may require risk. That takes guts.

Gerstner's advice: "Make decisions—not plans."

Are you giving attention to what your competitors are doing? What about other changes going on around you? Gerstner criticizes most companies as giving minimal attention to external risks.

Too many organizations fall into this trap. It's easy to think that internal decisions and actions fully account for the company's results. But this is a fallacy. Good strategic planners will spend a great deal of time, energy and focus on external forces.

For organizations that tend to focus internally, it may be advisable to bring in outside help. A third party can offer expertise and a fresh perspective as a non-stakeholder. But be forewarned: it's very likely that the information won't be benign. There will be threats to your business. Analysis will be needed and decisions will have to be made.

A final component of the external scan should be the development of contingency plans. Developing the right contingencies—ones that will actually work—will again require brutal assessment. You'll need to ask some tough "what if" questions.

This will probably come with one major objection: "How can we possibly know all of the potential contingencies?" The answer to this is to only develop one or two contingencies that could be disruptive in a major way. For example, a competitor is working on a new technology that could capture 15 percent of your market share next year. If that were to happen, what would you do?

Making a difficult decision like this immediately—rather than under the duress of an emergency situation later—could have a dramatic impact on your company's bottom line.

Your company needs a strategy. But, as the CEO or other key executive, you can't delegate this downstream and expect to see bottom-line results. It won't happen, for one very simple reason. They can't make the hard decisions that are required to produce a viable strategic plan. It doesn't mean they aren't valuable for other tasks, such as gathering and organizing data. But this is an exercise that requires all of the top company brass to get involved, roll up their sleeves, ask the tough questions, and make informed decisions.

All of the other pieces discussed in this article are important. They need to be implemented for any organization to have a viable strategic plan.

But one element is absolutely essential. Without it, any plan is doomed to fail. Yet oddly enough, it may be the most overlooked piece of the strategic planning puzzle.

What is this secret element?

The secret is this: You must convert the plan into action. After all, if you don't execute a plan, what's the point of even creating it in the first place? Amazing as it may seem, it rarely happens. And when it does, incredible companies are built.

Think of some of the great business leaders of the past few decades: Welch, Iacocca, Walton, Gates, and Jobs, to name a few. They led their companies first by developing great plans that required making tough decisions. But they didn't stop there. They put those plans into action and followed through. Each of them took calculated risks, accepted mistakes, adjusted his plan, and persevered in pursuit of it.

But they had one thing in common. They each had a strategic plan.

Do you?